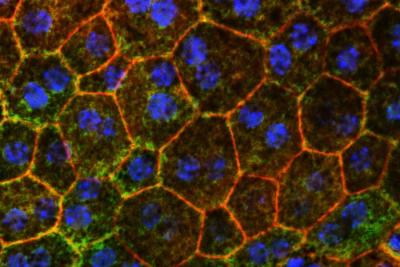

Fixing problems with cholesterol metabolism might help slow or prevent a common cause of age-related vision loss, a new WashU Medicine study in mice has shown. Pictured are color-stained retinal epithelial cells from a mouse eye, the first cells to die as age-related macular degeneration progresses. Credit: Tim Lee, Washington University

A new National Eye Institute-supported study identifies a possible way to slow or block progression of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of blindness in people over age 50.

The study, conducted by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and international collaborators, implicated problems with cholesterol metabolism in this type of vision loss, perhaps helping to explain the links between macular degeneration and cardiovascular disease, which both worsen with age.

Findings from the research using human plasma samples and mouse models of macular degeneration suggest that increasing the amount of a molecule called apolipoprotein M (ApoM) in the blood fixes problems in cholesterol processing that lead to cellular damage in the eyes and other organs. Various methods of dialing up ApoM could serve as new treatment strategies for AMD and perhaps some forms of heart failure triggered by similar dysfunctional cholesterol processing.

The study published June 24 in the journal Nature Communications.

“Our study points to a possible way to address a major unmet clinical need,” said senior author Rajendra S. Apte, M.D., Ph.D., professor of ophthalmology and visual Sciences at Washington University. “Current therapies that reduce the chance of further vision loss are limited to only the most advanced stages of macular degeneration and do not reverse the disease. Our findings suggest that developing treatments that increase ApoM levels could treat or even prevent the disease and therefore preserve people’s vision as they age.”

In macular degeneration, doctors can see cholesterol-rich deposits under the retina during an eye exam. In early stages, vision might still be normal, but the deposits increase inflammation and other damaging processes that lead to the gradual loss of central vision. In the most common type, “dry” macular degeneration, the cells in the central part of the retina can be damaged, causing a type of neurodegeneration called geographic atrophy, which is similar to what happens in brain conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease. Dry macular degeneration can turn into “wet” macular degeneration, in which abnormal blood vessel growth damages vision.

Geographic atrophy and wet macular degeneration are advanced forms of the disease that are accompanied by vision loss. Although some approved therapies for advanced disease are available, the disease process itself is not reversible at that stage.

A common culprit in eye disease and heart failure

In recent years, evidence has emerged that ApoM can serve as a protective molecule with known anti-inflammatory effects and roles in maintaining healthy cholesterol metabolism. With that in mind, Apte and co-senior author Ali Javaheri, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor of medicine, were interested in assessing whether reduced ApoM levels, which fall with age, could be involved in the dysfunctional cholesterol metabolism that is at the root of multiple diseases of aging, including macular degeneration and heart disease. They showed that patients with macular degeneration have reduced levels of ApoM circulating in the blood compared with healthy controls. And past work by Javaheri, a cardiologist at Washington University, showed that patients with various forms of heart failure also had reduced levels of ApoM in the blood.

To read further, visit WashU Medicine.