Researchers have developed lab-grown pig retinal organoids to test stem cell replacement therapies for diseases that damage the eye's light-sensing photoreceptors.

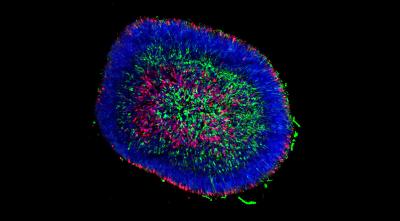

A retinal organoid examined at an early stage of differentiation shows different cells visualized by immunocytochemistry. Credit Kim Edwards.

Organoids are small tissue clusters — about the size of a large pin head — made up of hundreds of thousands of cells. They enable scientists to replicate cellular interactions in the controlled environment of a lab dish.

David Gamm, director of the University of Wisconsin's McPherson Eye Research Institute, says that stem cell replacement therapy using lab-grown photoreceptors is a promising strategy to combat retinal disease. The challenge is that stem cell treatments aimed at replacing photoreceptors need to first be tested in animals. Since human cells are not compatible in other species and are quickly rejected when transplanted, it’s difficult to assess their potential.

“Pig and human retinas share many key features, making pigs ideal for modeling human retinal disease and testing ocular therapeutics,” Gamm says. “By testing ‘human-equivalent’ photoreceptors in pigs, we can get a better sense of what these cells can do if they are not immediately attacked by the host animal.”

In a new study published in Stem Cell Reports, the Gamm Lab partnered with researchers at the Morgridge Institute for Research to develop lab-grown pig retinal organoids. They found that pig-derived photoreceptors shared many similarities with those made from human retinal organoids.

“This is the first time that people have made pig retinal organoids,” says Kim Edwards, a graduate student in the Gamm Lab and first author of the study. “And this was the first time that people have done a comparison of human versus another species of retinal organoids.”